What Is Plot? an Interview with Hilary Plum about her novel STATE CHAMP

Interview with Hilary Plum about running, protesting, and writing a novel in diary form.

Minor programming notes:

I was recently a guest on Sleerickets, a podcast about “poetry and other intractable problems,” hosted by

. Part one of our interview is here, where we spend most of our time discussing Toni Morrison’s 1993 Nobel Prize speech. In part two, we examine many topics broadly related to formalism in poetry. I encourage you to give the podcast a chance. It’s got over 200 episodes—a phenomenal run—that doesn’t seem to be stopping anytime soon.Back in April, for National Poetry Month, I published two poems in The Rumpus.

In January, I published a short story called “I’m Tom Hanks” (about how I’m actually Tom Hanks) in Post Road.

In May 2024, I published yet another poem about the moon in The Exposition Review.

I will also have a piece forthcoming in the provocative new anthology You May Now Fail to Destroy Me, edited by

and . Will alert when it’s available to pre-order.There’s probably more I forgot, but I’ll post them when I remember them.

This Spring, I got an agent for my first novel, which we’re currently revising together. Should go out to publishers soon. I will probably talk more about this book in the future.

Now onto the feature: an intro to the writing of Hilary Plum, some thoughts about plot inspired by her new novel, and a really cool interview with her.

The first time I hung out with Hilary Plum, we went for a run through the cornfields outside Northampton, MA. One minute in, I realized Hilary’s definition of running was actually running, and mine was more like jogging. I was only able to keep pace out of fear that she would think I was a loser. When we’d looped back where we’d started, exhausted, I suggested we go a beer. Hilary, running in place, said, “We could keep going if you want? I still have gas in the tank.” I smiled stiffly, a hostage to her athleticism and to my vanity. I think we continued for a while longer and then eventually did go get that beer.

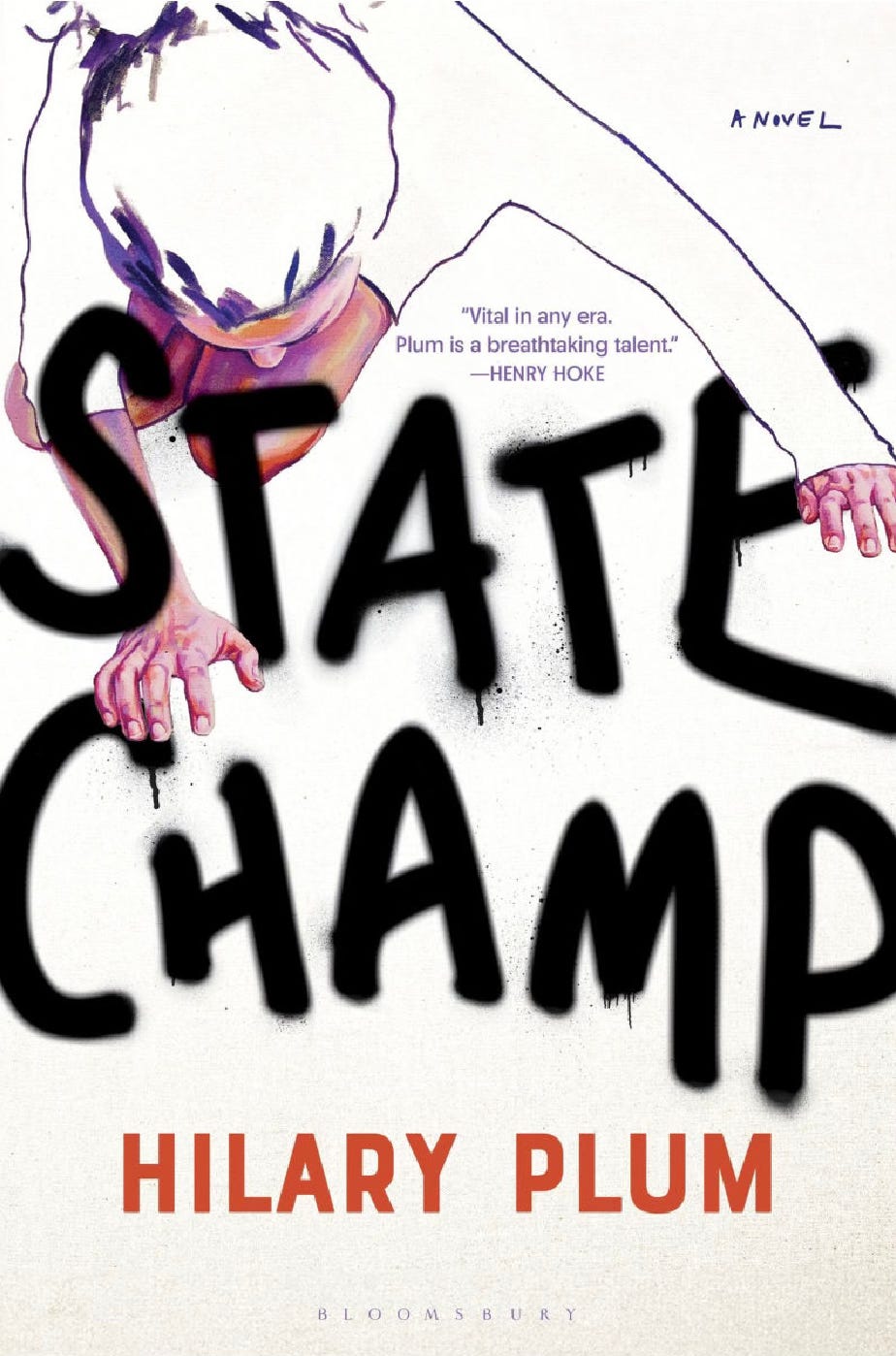

Hilary’s latest novel State Champ, just published by Bloomsbury, is about a washed-up cross-country star named Angela who decides to go on a hunger strike to protest the rollback of abortion rights.

Hilary’s books often chronicle war and American life in times of war. They blend journalism, fiction, and essay to morally clarifying effect. Avoiding trite narrative setups and payoffs, Plum exhumes America’s sin of complacency regarding the visible and invisible mechanisms of warfare. Although her books have a strongly progressive perspective, that perspective is restless and ferociously critical of progressivism when it is feckless, naive, or sleepwalking.

State Champ continues Plum’s examination of protest and politics, but in the context of abortion instead of war. And, instead of the experimental mode of her earlier works, the novel hews closer to conventional storytelling. We have a single protagonist (Angela) with a single objective: starving herself to protest the closure of an abortion clinic she is holed up inside of. Angela also narrates the action via diary entries, with each entry catching us up on the progress (or lack thereof) since the last. These entries build to a harrowing conclusion, all the while maintaining the plausibility of the diary format.

Angela’s situation is both unique and ordinary. Unlike most of us, she works at an abortion clinic. But like many more of us, she’s not a good worker, and no one really seems to like her. In this way, she reminds me of Eileen. As with that novel, I found the employment of a protagonist who isn’t lab-grown to be relatable a joyous reprieve from the plague of likability that burdens so many modern novels, shows, and movies. Nothing is easier to put down than a book whose first page is dedicated to making sure the reader knows the main character is broadly approvable.

Although Angela is not “likable,” she is heroic. When the passage of a new law results in the closure of the clinic she works for, she confounds everyone by holing up in the clinic and refusing to eat. The book begins on the second day of the strike with Angela describing what she is doing and why. We are then off to the races with an off-kilter protagonist/narrator telling her own story in all its ugly glory.

What Is Plot?

From the jump, there’s only a few ways State Champ could realistically end: Angela could stop her protest and resume eating, or she could see her strike through to the end, potentially dying in a way that would be painful to read about, especially in her unsparing narration. If she does back down, though, she gives up her fight, and it’s her fight against the odds that makes her protest so interesting. I don’t want her to back down, but I also don’t want her to die.

There seems to be two vocal camps when it comes to plot in literary fiction. (I hope the dichotomy I’m about to propose isn’t me just aimlessly straw-manning something that doesn’t exist so I can have something to piss on, but, even if I am doing that, it doesn’t matter, that’s what substack is.) In one camp, you have what we might call the “screenwriting scolds.” They think plot is essential and the only good way to reveal character. Like anyone who pounds the table about any way to write, these people are very annoying, and that is why, although I identify with this camp more than the other, I only do so reluctantly.

The other camp, let’s call them “literary snobs,” are the people who say, often with grating piety in podcast interviews and the like, that they eschew plot and think of it as a dirty concern, if they think of it at all. These are the people for whom plot is in bad taste or somehow reflects a lack of intellectual or philosophical sophistication that they aspire to (and which can only be attained by chasing “language,” “character,” or some even arcaner form of vibes.) These people are also annoying but also have a right to their opinion.

Not that anyone asked, but here is my take: We have all read bad commercial books with tons of plot that was inauthentic and transparently manipulative and evocative of nothing but the author’s limp wish to collect gold coins or something. We have also all read literary books that were insufferable because there was no plot, or they fumbled the plot they tried to have, or by their avoidance of plot, they were still not saved from being transparently manipulative or inauthentic in the numerous other ways it is possible to be those things, evoking little but the author’s desire to become an aesthetic god-ling untainted by the sin of clearly defined dramatic stakes, and which made their book feel like a hollow exercise in style with nothing to say about anything.

We have also all read a few of the 1% of commercial books whose plots evoke stunning intellectual complexity and emotional authenticity, and, we have also all read a few of the 1% of literary novels that eschew plot entirely only to secretly have a great plot they pretended not to have, or don’t have any plot at all but leverage so forcefully all the other elements of storytelling that they astound and haunt us in ways a conventional plot would have hindered. Or which, had the author cared about plot at all, would never have been able to be written.

Either path can work, in other words, and we also all know that.

I suppose I say all this so that when I say State Champ has an interesting and effective plot, it will sound like the deep praise I intend it to be, especially for an author with so much to say about American politics and who has done so much hard time, so to speak, in the experimental fiction mines…

I had no idea how State Champ would end, which is the easy part of plot. Even bad books can surprise you, and many do. From the first page, however, I also wanted to know how it would end, which is the hard part. This to me feels like a good working definition of a conventional plot.

But State Champ does something else that we could use to create a working definition of a good literary plot. Of all the different endings I could imagine as I read, I wasn’t even sure which one I wanted, which one I was rooting for, or how any of them could wind up being satisfying. The tension of not knowing how it could work out for Angela, in any way, while suspecting that Hilary would somehow delivery a satisfying ending to the story, was the real treasure of the novel. As I sped toward the finale, I continually asked myself what I wanted to happen, and what that said about my own political imagination.

This is my ideal reading experience.

Interview with Hilary Plum

ML: Why do athletes make good protagonists for protest stories?

HP: I think we use athletes to play out our relationships to success and failure, which gives them a power we also don’t want them to totally have. They’re heroes, but only on a specific stage, and because the way in which they are extraordinary will inevitably fade, we don’t ever have to feel threatened by that power. Most athletes become disposable, no matter how much money they might be making right now.

Athletic success also tends to be more open to people across races and classes and backgrounds—but then, once you’ve achieved success, you’re supposed to stay in your place. You’re supposed to generate only the good feelings (individual or team glory, vicarious glory for viewers), not bad feelings (reminding us about racism or CTE or eating disorders or wealth inequality).

So maybe it’s especially powerful when athletes—the workforce producing those happy, glorious feelings—choose to assert their right to be a person and thinker in the world when their fans and employers just want them to be entertainers. I’m thinking of how outraged and inspired many people were when Colin Kaepernick protested police brutality, claiming his right to speak and be heard with opinions about his own life as a Black man as well as an NFL quarterback.

ML: One thing that is different between Colin Kaepernick and the protagonist of State Champ is that Angela is not famous or even very good at her job. What was appealing to you about using an abrasive protagonist for this kind of story?

HP: Initially, I wanted to write about a bad employee out of curiosity. I guess I wanted to learn more about what it would be like to be a bad employee. Then as the novel went on, a new reason emerged. It became important to me that Angela wasn’t some saint anyone could project themselves onto—because abortion workers shouldn’t have to be saints, and people who get abortions shouldn’t have to be saints. On the one hand, yes, it’s powerful to share abortion stories—as there’s an ongoing movement to do—because that public discussion helps dispel right-wing myths about abortion and makes it harder to turn the people who need, get, and provide abortions into cartoon villains. But you also shouldn’t have to justify it to anyone. The right to privacy, to healthcare, and to abortion applies as much to a bad worker as it does to a good person whom everyone adores and says good things about. I hope Angela is a bit of a reminder that no one should have to be anyone’s idea of a good woman with an uplifting story—a good professional worker with a self-sacrificing job—to deserve their bodily autonomy and to participate in the world on the basic terms of that autonomy, or to express themselves politically.

ML: You were a competitive runner. Did you ever win a state championship?

HP: I worked hard but never achieved greatness. My cross-country coach in high school understood this inspiring tragedy: he used to call me and my friend “the workhorses” of our cross-country team. We were ranked nationally, and we did win a state championship. I was fifth on the team, so I wasn’t elite, but I did score (in cross-country, the top five runners on each team score). That’s as close as I ever got to matching Angela.

ML: What does running demand of its champions that other sports do not?

Running is simple. “Run fast, turn left,” as my track coach used to say. Running is also unsparing. The times don’t lie. When you finish a race and see your time, you have an objective measure of how you ran, which is humbling. This is less true in team sports, where you never know how a game might have changed had one thing gone differently, had your teammates performed better or worse, had you played a different team, etc. In running, you can compare any of your performances to those of the best athletes in history. Whether you finish first or last, you both ran 400m, 1600m, 5k, etc. And you both feel like shit afterward. And you can talk to each other about it. So I feel like running requires heightened self-awareness, heightened comfort with objective measurement, but it also offers greater potential for solidarity among competitors from the most elite to the most green, compared to other sports.

ML: At one point in State Champ, Angela calls a random filing cabinet “unpopular,” as if she is both rating and disparaging all the office equipment in the clinic. It reminded me why I love judgmental characters. I think this is how most people are in real life, privately. We all have that one bath towel we hate, that one stupid-looking tree in the park that pisses us off and also makes us feel guilty for judging it. Can you describe what it was like to write this description? Were you hyped because you’re obsessive about finding evocative yet casual yet character-appropriate adjective+noun combos? Or was it more incidental and just sort of happened because that’s just how Angela talks and you were just channeling her voice?

HP: I think Gertrude Stein said that adjectives are what writers most like to change in each other’s writing. From that, maybe we can infer that adjectives are what we most identify with in our own writing (and may be what we’d most like to change about ourselves). I swap adjectives intensively when revising, while also trying to “go big” during initial drafting, trying to land on one fresh adjective that will enact both materiality and perspective while also being surprising (including to me).

About the filing cabinet, I agree with everything you say, and I want fiction to represent that humblingly mundane experience of our actual world, which is also then our politics, our economics, our law, our whatever. I do have a bath towel I hate. We could all precisely recreate places we’ve boringly worked in from memory. I think all the time about the bugs that used to try to come through the window when I worked at Dairy Queen in 1999. I have never seen those exact insanely large bugs again. Is that because of climate change or leaving New England or the attraction of ice cream? This is the stuff of fiction, the way a detail can call up those questions and connections without overdetermining them, keeping them open and alive.

ML: If State Champ were a sensitive, arthouse film made by a team who deeply admired the material, who would you want to play Angela, Dr. Park, Janine, and, in flashbacks, Angela’s mother?

HP: I think the best person to play Angela would be Michael Fassbender. I was talking about this with Callie Garnett, the novel’s editor. I wouldn’t want a young woman actor to play Angela because it would be too hard on her, to diet like that, and it could easily veer into some disturbingly pro-ana content, like just more romanticizing thinness for women and girls. But Michael Fassbender already did it to play Bobby Sands in Steve McQueen’s Hunger, and that was a great performance. If we’re casting Irish men, Jamie Dornan would be an incredible Janine. Angela’s mother, Cillian Murphy.

But I just remembered there are some allegations about Fassbender in his private life, so that’s a problem for our feminist film here. And these aren’t even indie actors (or they’re indie crossover), so I haven’t answered your question.

I would like this film to be directed by Ken Loach. I don’t know that it would work, but I love the combined playfulness and desperation of his later films like Looking for Eric and The Angel’s Share. In general, I think an older actor playing young could be a good Angela. Someone like Hiam Abbass, who has an incredible physical presence while also conveying a private sense of humor and judgment. I am most impressed with actors whose outward performance can somehow suggest an opaque private interiority, a deep latent capacity for humor. For this reason, we could also audition Jon Hamm.

ML: If they made State Champ into a big budget, mainstream movie—taking everything complicated about it and sanding it away to make it 99% stupider and more marketable—and they let you have a say in casting, but you could only cast huge stars and just pray they’d have the chops to preserve some sliver of the novel’s nuance—who would you cast for Angela, Dr. Park, Janine, and Angela’s mother?

HP: OK, in this case I think Angela should be Amber Heard. Dr. Park, Sandra Oh, especially because it would call back to Christina Yang on Grey’s Anatomy. Janine, Angelina Jolie. Angela’s mother, maybe also Angelina Jolie. The cop should be played by Jake Gyllenhaal, obviously, or a random younger Wahlberg. John, by LaKeith Stanfield—who could also play Angela in the indie version, now that I think about it. He is amazing.

ML: Thank you for humoring those frivolous casting questions. The one is less frivolous but still a little frivolous. One of my favorite side-characters is Janine, who is on one level Angela’s “antagonist,” a self-righteous anti-abortion person counter-protesting her hunger strike. But Janine is also trying to connect with Angela as an individual and maybe save her from feeling alone. On page 136, however, Angela describes Janine as someone who looks like she would “hold you down and tuck marshmallow fluff into the corners of your eyelids.” This was the only time in the book where Angela’s wild descriptions eluded me. I thought a lot about what this could mean. At the risk of gauchely asking a writer to explain their own writing, what did you mean by this description? And please feel free to tell me to fuck off if it’s not interesting to you to be asked this.

HP: I love this question because I remember feeling satisfied when I wrote that line but not why. Here’s my best guess: it’s because Janine is thorough and effective and maternal (at least, in her own terms) and cruel. Whether Janine understands herself as cruel, or intends to be, is more of an open question. I think amid my personal pantheon of snack foods, I have two strong associations with marshmallow fluff. One, fluff is an indulgence among grown women I respect, including myself—something we enjoy buying and eating—and it’s made more indulgent because it’s so nostalgic and meant for children, or marketed to children with a wink to the rest of us. This is a whole aesthetic, a food that adults eat as a “guilty pleasure” because it’s a food from childhood and for kids, but it’s unhealthy for kids, so it’s actually better that I, a 40-something woman, am eating it. At least this is what I tell myself. Two, I associate fluff with a certain friend’s mother from childhood, who would serve lots of fluff and other classic junk foods to her kids, but then also intensely body-shame them. I’m not saying fluff is necessarily bad for you (I tend to think no particular foods are “bad”), it just seemed a little unfair and psychically charged to give your kids a lot of pure sugar and processed foods while constantly hassling them, the girls especially, about their weight and health. So I guess fluff is kind of a sick food, at least to me. As for the eyeball thing, I think this is because Angela thinks Janine’s work in the world, opposing abortion, is pretty intimately violent actually.

ML: You just taught me what marshmallow fluff is. I saw it in the store the other day—for the first time ever—after reading your response. I’d never even heard of it, and yet it’s probably been there, my whole life, on the shelves of every store I’ve ever been in. I thought marshmallow fluff was just Angela’s colorful way to say marshmallow, so I was imagining Janine pack whole marshmallows into Angela’s eyelids, which is more absurd but also maybe conveys something not too far from your intent. It must be an insane coincidence that I’ve simply never had or heard of marshmallow fluff until now. It feels satisfying to learn that the only line in your book I was confused by was the result of having never intersected with this ubiquitous grocery store product. I feel like awareness of marshmallow fluff is a kind of bullet that reality has probably been shooting at me my whole life, from every angle, but which I have unknowingly dodged, and now it’s moving right through me, and I can feel the weight of all the coincidences I still don’t know about exerting their pressure on the shape of my life the way dark matter shapes time and space even though we don’t know what it is.

HP: …

ML: What were the plausibility challenges of writing this novel in the form of a diary?

HP: My main anxiety was the natural unbelievability of that form. Diaries, like letters, are one of the classic forms of the novel, even though they’re hilariously implausible, because you have to do all this plot and exposition in this constrained form without breaking the spell. My main strategy was to never leave the diary form. Some agents and editors I queried, for example, suggested including a separate subplot alongside Angela’s diary, but I thought that if the reader ever left the diary for a more “realistic” scene, they would notice the diary’s unrealistic qualities upon reentry. Transitions are when we can glimpse the man behind the curtain.

Another challenge to realism was the plausibility of Angela being able to keep writing while starving. For example, Bobby Sands stopped keeping his diary on day 17, I think, or something near to that, because he got too weak. Also, can you even write on medical exam-table paper like Angela does? Or is it too waxy or too thin?

Lastly, for me, this novel is a means to think together about abortion and bodily autonomy and freedom and gender, more than it is a realistic account of working at an abortion clinic. That’s OK with me, or even right, in my opinion, because novels are supposed to do something different than journalism, than nonfiction. All these are things I weighed while trying to work this form and commit to its limits and possibilities.

ML: Last question. While reading State Champ, I wrote in my notes, “How are we connected to our opponents ‘in unseemly ways’?” I’m not exactly sure why I wrote this, and I’m not sure why I put ‘in unseemly ways’ in quotes—because these are my words, not yours. Regardless, what’s your take? How are we connected to our opponents in unseemly ways?

HP: It is profoundly oppressive and epistemologically wild how much our understanding and action are shaped by those whom we oppose (or try to). In some cases, we might think of our relationship with our opponents as more autoimmune than purely adversarial; in others it’s more about subjugation and even elimination, but an entangling may still occur and matter later. The terms of a debate often pre-exist the parties, and the parties’ ideas of themselves are caught up in the thinking of the other, or how they think of the other. It is unseemly. As the great poet Mahmoud Darwish says (trans. Joudah): “And everything that exceeds its limit / becomes its own opposite one day.”

And our opponents are also just people, people whom we could have been, speaking of coincidence. There’s an intimacy you have with an opponent because an opponent permits you to know who you are and to understand what in your life has actually been a choice that defines your agency. This is a sort of gift you give each other, even though you don’t want to give or receive gifts from that person, and the stakes of your enmity are much higher than any personal self-understanding. Angela and Janine have this intimacy a bit, I think, or at least Angela relates to Janine this way.

So, for example, I don’t have any disagreement with people who oppose abortion—a personal opinion anyone has a right to—until they try to deny abortion to others. Then my disagreement with them is entire. I don’t hate them, unless I know that they know or suspect how cruel the consequences of their actions will be. In many cases, I suspect that they are actively refusing to acknowledge these consequences, and although that may not be cause for hate, it is a cause for opposition—for an unseemly kind of demand on the other that they truly account for themselves and the consequences of their actions. This kind of demand—that we give an account of ourselves on another’s terms, or in answer to another’s question—may often feel unseemly. But these demands, these accounts, are necessary for us to live together.